Expressways are some of the largest manifestations of urbanization that you will encounter while moving about a city. Most cities in North America basically require you to interact with them in order to get around; you likely have to pass under or above them even if you are traveling without a car. These beasts are likely one of, if not the, biggest construction projects in the history of any given metro area, requiring the demolition of many square miles of land to build. Historically this was done in the poorest neighborhoods, often used to purposely displace minority communities or to create a barrier between white and minority neighborhoods. Louisville is no exception to this, but there is often little discussion of the history surrounding expressway construction and its consequences in Louisville.

This subject matter was briefly touched upon in our Field Notes series on urban renewal in Downtown Louisville, but the geographic scope of that was limited. Expressways dominate significant amounts of land outside of downtown as well, attempting to get commuters in and out of the urban core as quickly as possible by car; whether this is an effective way of mass commuting is a whole other rabbit hole, but this is the method the federal, state, and city government(s) adopted en masse in the mid-20th century.

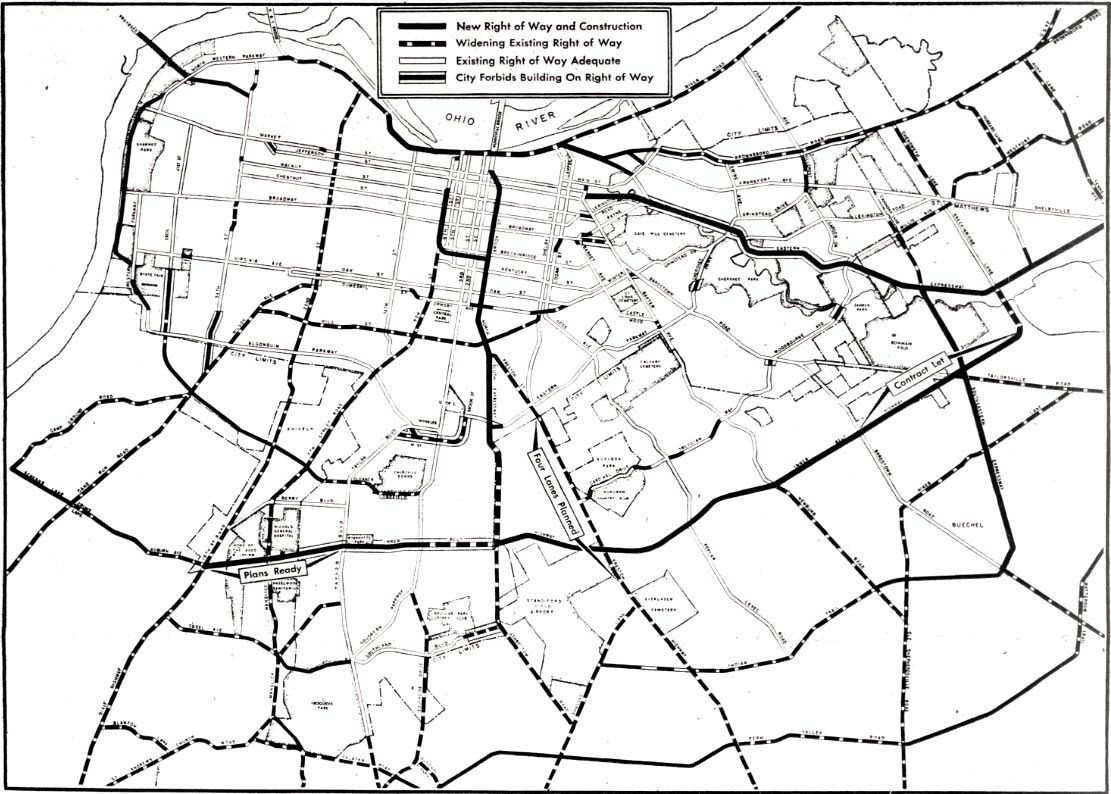

An expressway system was envisioned for Louisville in some capacity by the mid 1940s. Original discussions focused on the North-South Expressway, later I-65, and its necessity in alleviating downtown traffic. As we entered the 1950s, plans for expressway construction expanded rapidly, with city and state officials putting themselves behind a variety of projects: the aforementioned North-South Expressway, inner belt expressway, outer belt expressway, east end expressway, west end expressway, and riverside expressway. The scope and routes of many of these projects would shift as planning went on as new challenges, opposition, and scandals arose. Some other expressway projects were also proposed, such as a “cross-town”, that ended up falling through.

The story behind these projects and the displacement they brought about is lengthy, so this piece will only focus on one of the most pivotal: the North-South Expressway.

North-South, The Downtown Divider

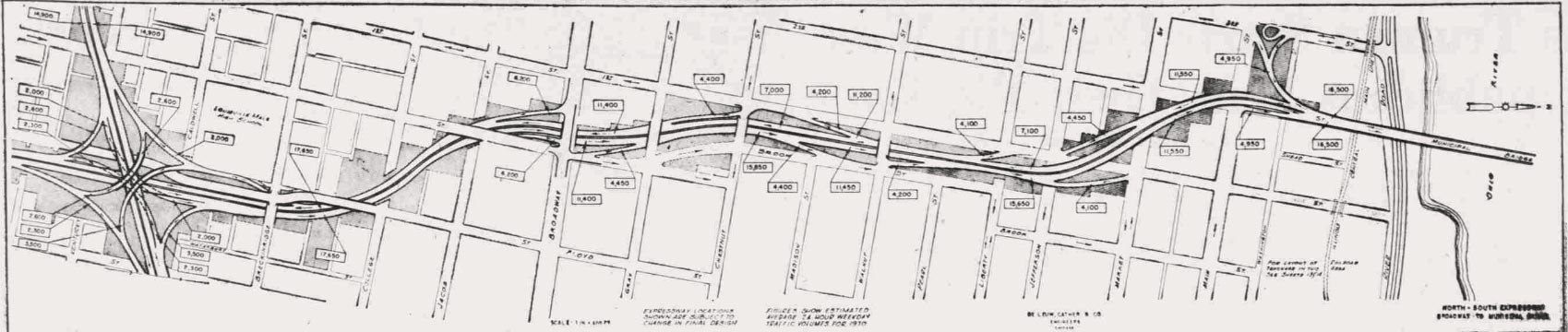

By early-1945, studies were underway to evaluate where expressways would be built in Louisville. It was pretty quickly decided that there would at least be two primary routes: an east-west expressway and a North-South expressway. The North-South had more initial momentum, with the goal being to build it before any east-west route. The goal for this North-South route would be to connect the Municipal Bridge (now Second Street Bridge/George Rogers Clark Memorial Bridge) to Standiford Field (now Muhammad Ali International). This initial goalpost led to the expressway having many names: Second Street Expressway, Midtown Expressway, Clark Memorial Expressway, Municipal Bridge-Standiford Field Expressway, and of course the North-South Expressway.

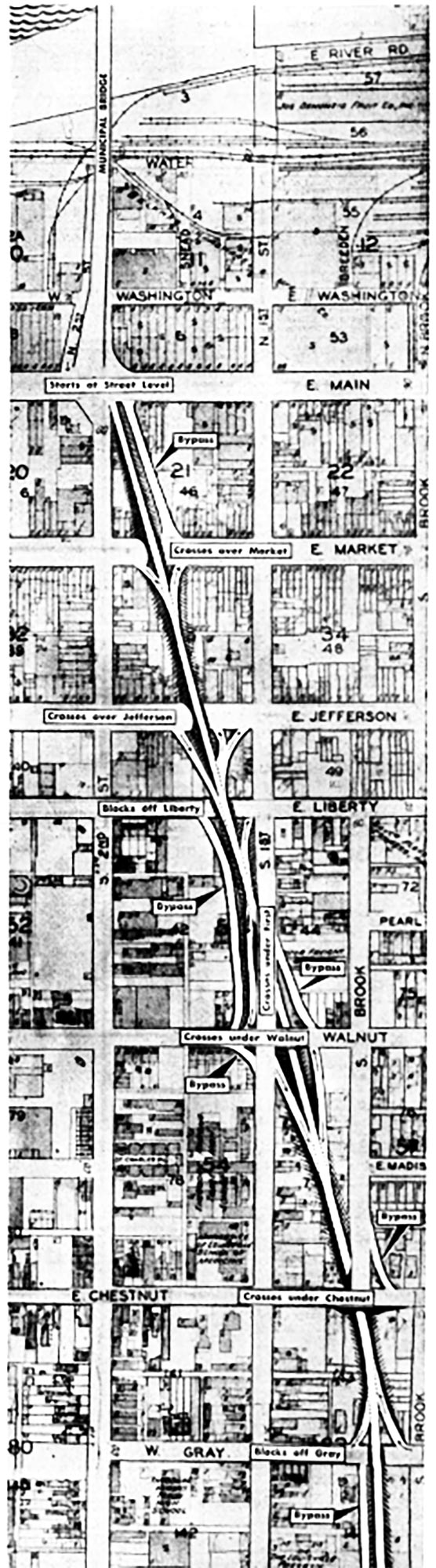

Although studies had only recently started, plans were “fixed” for the North-South route by July 1945. Initial plans had the expressway starting by Eastern Parkway before heading towards downtown, winding over and under downtown streets to meet the intersection of Second Street and Main Street. State Highway Engineer Tom H. Cutler estimated the project would cost around $8 million, which is around $143 million today.

The expressway project would immediately become subject to vehement debate. Board of Alderman (predecessor to Metro Council) President, C. Paul Downard, called it a “monstrosity” and suggested widening lanes on current highways and utilizing public transit to relieve congestion. There was also a good amount of skepticism from local businessmen, among them was A.J Stewart, Vice President of Citizens Fidelity Bank & Trust Company, who aired one of the more common critiques:

“Every time you give a fellow a better way to get out of a city you’re adding to decentralization”

These critiques were quelled by an update that the expressway would begin in the south and move north as funding was made available, meaning downtown may not be affected for a few years. Those in favor of the project also made their arguments, the biggest proponents usually being highway engineers and government officials, including the mayor. H. W. Lochner, a highway engineer from Chicago who worked on surveys for the new system, argued the opposite of Stewart, that the expressways would actually slow down decentralization:

“The biggest returns will be to the downtown area and will help stabilize downtown business volume”

The North-South route had more opposition at the time than most expressway projects, besides maybe the east end route. The planning process was getting dragged out by opposition and the typical bureaucratic issues. Leaders of the previously mentioned Citizens Fidelity Bank & Trust Company were among the most common (or at least most documented) detractors, meeting with city officials throughout the planning process to voice opposition. It is worth noting that this group of skeptics and many others were not *against* the concept of an urban expressway, but rather wanted it to approach downtown from a different angle, not cross Broadway, focus on “blighted” areas, or had other more logistical concerns. Citizens Fidelity Bank & Trust, in particular, was just more fond of an east-west route rather than a North-South.

While city officials were bullish on the North-South project, uncertainty continued to build. In a 1947 event with the Louisville Area Development Association and the Urban Land Institute, not a single attendant voiced support for the new spinal expressway. By the end of the same year, approval would be given for other expressway work while the North-South route was officially delayed.

From this point, plans for the expressway meandered as it was clear construction would not be starting any time soon. There was a proposal to build an overpass that connects to the Second Street Bridge in the interim, which fell through. By 1949, officials were literally starting all over again [2] with a comprehensive streets plan. The North-South route did not change much, though, although a very notable addition was a downtown expressway loop. This would have an interchange placed near Brook and Breckenridge Street, allowing drivers to take an expressway west over Old Louisville until the expressway curved over towards Seventh Street and eventually meets with the “Riverside Expressway” (which is worth of its own article). Later plans would shift this loop quite radically before eventually eliminating it.

Momentum finally seemed to be on the side of city, state, and federal officials. In early 1951, the Board of Aldermen were so confident as to begin seeking to freeze development within 200ft of the expected route. Despite this, the final route had not actually been finalized [2]. Later that year, preliminary plans were eventually released and approved, following the expected route.

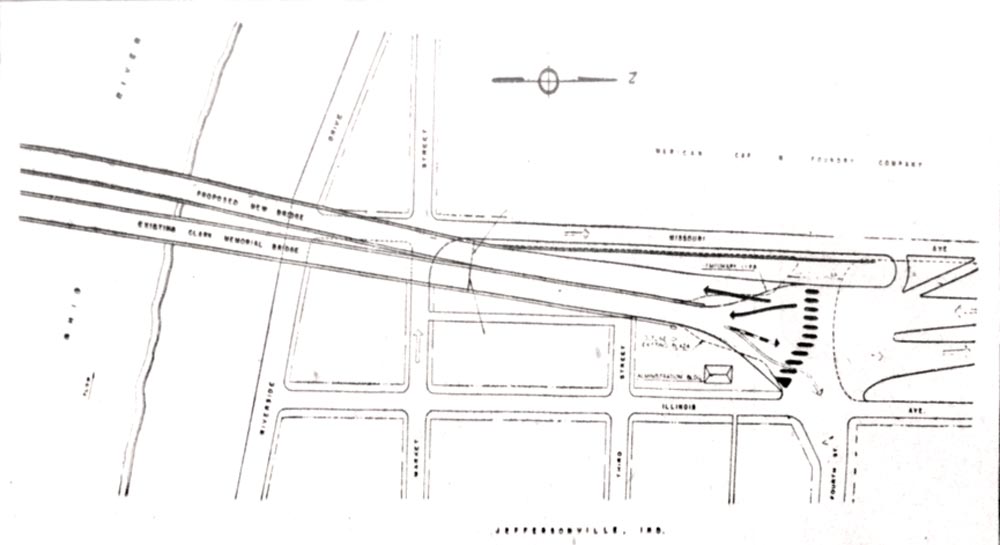

The renderings and maps above so far have been quite different from how we know I-65 today, but by late-1951, the idea of building an entirely new bridge was being entertained. Two new bridges were eventually in the cards, which made planning for the North-South route practically impossible until a decision was made. In late 1953, the Municipal Bridge Commission recommended the construction of two new bridges, although only one would connect to the north-south route and it would just be put right next to the Second Street Bridge.

Louisville Mayor Broaddus announced the project would be delayed, again, in early 1954. Plans were up in the air once again but most concerns around the expressway were related to the northern end in downtown. Officials could reasonably start planning for and even constructing the southern portions. Mayor Broaddus was hoping to start construction on the section between Eastern Parkway and Woodbine Street. It actually seemed that work would finally begin in late 1954, as the city began to raze buildings [2] [3] [4] in Old Louisville and Shelby Park in the path of the future expressway.

Construction of the southern three and a half mile portion of the North-South required less demolition than the future northern portions in spite of it taking up the most land. This is largely because much of its berth was covered by lower-density land uses, although the section that covered portions of the urban core required significant razing. An exact figure for the total number of structures is never given, although we can get a low-end estimate from coverage at the time: at least 65 structures were demolished, 54 of which were homes. Urban affairs reporter Grady Clay would later write that around 200 families were displaced, so the actual number of structures was likely higher. A 123-year old Hebrew cemetery was among the lots bought out, although they were not provided funds to move the graves.

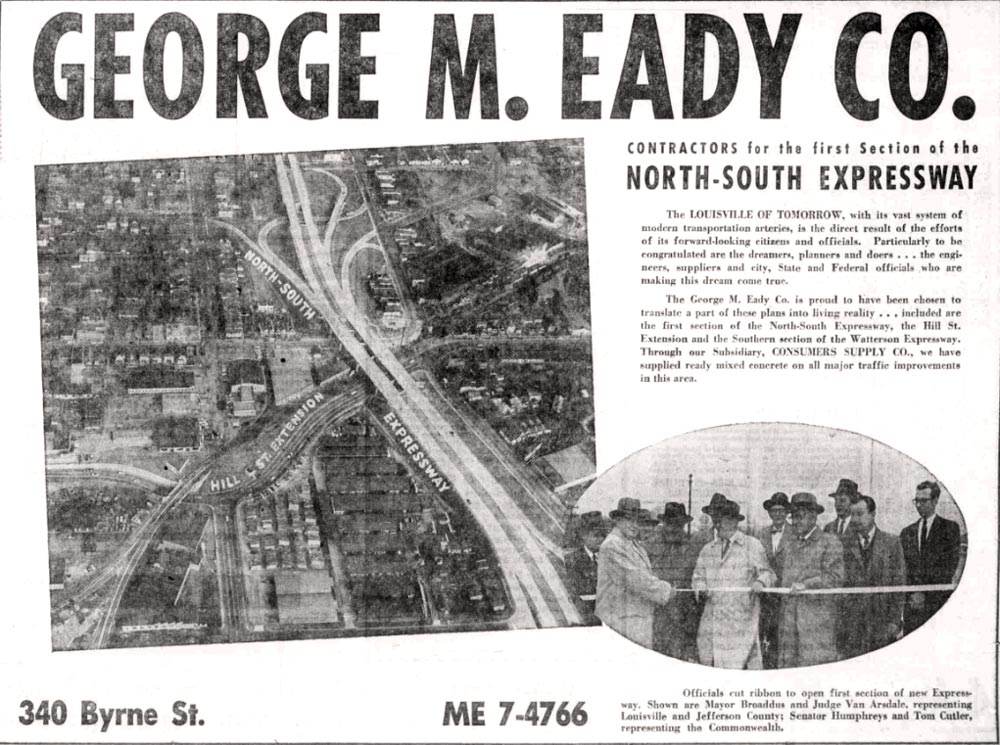

By May 1955, ten years after initial proposals, bids were finally out to construct portions of the North-South Expressway. Even more bids were going out to demolish the buildings that were in the way. Work on the expressway itself would begin by the end of the year, split into three sections costing approximately $9 million or $107 million in today's dollars. At this point, most political and legal barriers had been conquered, which should allow relatively quick completion of construction.

Towards the end of 1956, it seemed more and more likely that a new bridge would be built connecting Louisville and Jeffersonville. State officials were moving towards rerouting [2] the North-South’s downtown portion more to the east to meet with the new bridge rather than the Second Street Bridge. This would require construction of an interchange close to the riverfront, as this would likely meet with the planned riverside and eastern expressways (I-64). As this shift was ongoing, construction on the southern section of the North-South was wrapping up.

With the expressway opening soon, planners found it necessary to alter traffic patterns by the termination point. Portions of nearby streets became one-way, many of which remain one-way to this day. The first section of the North-South would open on December 17, 1956, although this was only between Woodbine and Gaulbert. The “full” expressway would open on August 30, 1957.

As the opening approached, more planning was underway on the northern portions. City and state officials wanted to immediately get to work on inching the expressway towards the Ohio River. An extension of the expressway would be announced before construction even finished, having the North-South stretch into downtown and terminating at Chestnut; this would require the city to buy (and demolish) around 275 properties for millions of dollars. Unfortunately there doesn’t seem to be much detail on what specific structures were demolished for this extension.

This extension would face some of the same problems as before: unhappy businessmen, displaced families, legal troubles, and logistical issues, but it only took them around a year to get started rather than ten. Bids were already out by mid-1958 and construction would begin the same year. This go around, construction would be more block-by-block with completed portions opening as soon as feasible. In the process, hundreds of structures would be razed to make way. The final portion opened on November 23, 1960; the North-South now extended from the Watterson to Chestnut Street, but there was still more to come.

I-65 as we know it today was beginning to take shape after the opening of the Chestnut expansion. Plans from 1959 basically show the expressway as it is today, minus the Abraham Lincoln Bridge which opened in 2015. The last thing left to do was to build out the rest of the expressway out towards the river, having it meet with the riverside expressway and a new bridge to Jeffersonville.

As downtown had such a high density of structures, the extension towards the river would require the demolition of hundreds of structures regardless of how it was routed. The land alone would cost around $8.1 million or around $109 million in today’s dollars. The razing would begin not long after. 315 buildings would have to be destroyed, 76 of which were residential and were home to around 300 families.

At this point, 15-years after initial proposals, the political process was more streamlined. Some opposition formed, once again from local businessmen, but they did little to slow things down. The logistics of tearing down hundreds of structures in a historic downtown was more complicated, however. It took until mid 1962 to tear down most of the structures, with work beginning on the expressway itself in September of the same year. Within a year, construction would be complete on both the new Kennedy Bridge and the final portion of the North-South expressway. Almost 20 years after initial proposals, one of Louisville’s biggest manifestations of the built environment was complete.

Legacy of the North-South

Urban expressways have a profound impact on the built environment, their footprint outmatching pretty much any other structure in a given city. The North-South Expressway was the first to barrel through Louisville’s urban core, defining much of the city’s urban form to this day. A project of this magnitude required demolishing vast areas. From the numbers we have of all the different sections of the North-South Expressway, at least 655 structures were destroyed (or in rare cases, moved somewhere else) to carve out land for its construction. At least 500 families were displaced, which was probably around 1500 people given the average family sizes at the time. These numbers are low-end estimates, and do not even include those who may be indirectly displaced by their workplace having to relocate, having to move to stay near to their directly displaced family, and so on. Many of the areas surrounding the expressway would depopulate in the coming years.

Much of the expressway system ran through redlined black communities. One of the most affected neighborhoods was Smoketown, which was bisected by the North-South. The neighborhood was once one of the most densely populated in Louisville, hosting a population of 15,000 all the way back in 1880. Now the neighborhood is home to around 2000 people, and much of the population decline occurred directly following the construction of the expressway. Our past series on urban renewal in Louisville covers more about the extent to which minority communities were targeted by urban freeway projects.

You could easily write a book about urban expressways in Louisville and the ways they affected the city’s population. The expressway’s off-ramps create some of the most dangerous intersections in Louisville, depress property values, increase air pollution, and much more. While this post has been self-contained, the extensive history and impacts of our urban freeways may be covered more in future pieces. The history of Louisville’s built environment can be under-covered despite its profound impacts on human health and how we go about our lives.